Systemic Bankruptcy, or How We Got Into Our Present Financial Mess, And What to Do About It

Societies, like many other natural phenomena, manifest a cyclical nature. They are born, they grow, and if not interrupted by natural disasters or conquest by neighboring societies, they mature, grow old, and die, giving rise to new societies. During the final phases of decline and death, their economies typically manifest several changes that signal the advance of old age and collapse. Among these are a change in the nature of their money, a change in the nature of their monetary system, and an increase in overall levels of debt, as compared to the general level of economic activity and accumulated wealth. As the sum total of debt throughout the society grows, relative to the sum total of income and assets, individuals and organizations within the society find it harder and harder to pay off, pay down, or eventually even service their share of that debt burden. Increasingly, promises that have been made to service and retire debts cannot be made good upon, and individuals and organizations in increasing numbers begin to fail and default on their debts. Since the failure of a debtor to pay back or even merely keep current on his obligations, denies his creditor a stream of income, or even worse return of monies lent out, the default of a debtor can cause the failure of his creditor also, because his creditor also usually has debts to service. If the overall bankruptcy rate in a society reaches a sufficiently high level, a positive feedback loop is established, and the bankruptcy rate increases still further. An economic chain reaction ensues wherein very rapidly almost every person and organization in the society goes bankrupt almost simultaneously. This is “systemic bankruptcy”, and it can happen in two ways: Either almost everyone goes bankrupt, or, the society’s money becomes worthless. Which of these two paths to systemic bankruptcy is realized, depends on the choices made by the rulers of the society. Usually, the path chosen involves total collapse in the value of the money. This zeroing out of the value of the society’s money, is made possible by the changes in the nature of the society’s money and monetary system which occur years or even decades before the onset of systemic bankruptcy.

What is Money?

Money is a commodity used in commerce as a medium of exchange to settle debts, and as a store of value over medium to long periods of time. Historically, money evolved in the barter marketplace to solve the “problem of coincidence of wants”. In a barter situation, you may have a surplus of something and want to exchange your surplus item for some other item you think you lack. So you go to market, knowing that there may be others there with the thing you want, who might want what you have. You search throughout the marketplace, looking for someone who wants what you have to offer, and also has what you happen to desire. If you find that other person, and the two of you can agree on the terms of the exchange, the exchange takes place and both you and your trading partner (your “counterparty”) go away happy. Both of you now consider yourself better off — richer — than you were before the trade took place. This is how wealth is created and distributed throughout a society. These voluntary exchanges, repeated countless times between countless people, are how a society grows wealthier with time.

If you do *not* find a “counterparty”, then your search is fruitless, and you leave the marketplace still in possession of your surplus item, and lacking what you came to market to obtain. You did not coincidentally find someone who had what you wanted, and who wanted what you had to offer.

What is money, then? As stated above, it is a commodity, but a commodity with a special property: It is the commodity that most people in the marketplace will be willing to accept in trade for whatever they happen to bring to offer in the marketplace. This realization that there is one commodity that most people will accept in trade, comes about naturally as people engage in repeated exchanges, and notice what most other people ask for in trade. The discovery of this one commodity solves the problem of the “coincidence of wants” described above. You can go to market with whatever you have to offer other people, knowing that they will have some of the universally accepted commodity to offer you in trade. You are willing to accept this commodity simply because you know that, it being the most universally accepted commodity, you will be able to offer *it* in trade for what *you* want to buy, even if you have to go to a different person in the marketplace or even go to different market on a different day. You can expand your trading activity across a wider range of places and times, by accepting and offering that special commodity in trade. When that special commodity is formed into standard recognizable units of quantity, it becomes money. Historically, the special commodity has been one or a combination of three metals: Copper, Silver, and Gold. These metals make good money because of their inherent value as commodities, and because of their physical properties: They are scarce bot not too rare, they are useful for making things and therefore desirable to have, they are uniform in nature (one lump is like any other lump), they easily formed into convenient shapes, and they are stable and long lasting and non-toxic.

What is debt?

Debt is a promise to deliver an asset made by one person to another person. (“Person” here can also be an organization of people bound together in common purpose.) The asset to be delivered from he who owes to he who is owed (from the debtor to the creditor) can be anything the creditor considers to be valuable. Often, the asset is, of course, that special, universally accepted commodity, money.

Consider how this works in detail. Suppose you go to a restaurant and order a meal and consume it. As you are eating the meal prepared and delivered to you, you incur a debt to the restaurant. At the end of your meal, the restaurant has delivered an asset to you, namely, your food. You have incurred a debt to the restaurant in exchange. This debt was assumed by you when you ate the food.

To pay for your food, you must deliver an agreed upon asset in exchange, which is usually money in a certain amount. As soon as you hand over the money, the debt is destroyed. The debt was brought into existence when you ordered and consumed the food, and then eliminated when you delivered the money to the restaurant. *The transfer of money is what eliminates debt.* That is the first essential property of money: It is what destroys debt.

There is one and only one other way to eliminate debt: To simply not pay it off. In this case, the debt is eliminated when the creditor gives up trying to collect payment, and he “writes off” what you owe him.

Suppose now you have eaten your meal but find you are short of money in your wallet.

You cannot pay the full amount. Instead of simply refusing to pay for your meal, you make arrangements to pay for it by other means. Here is where the other essential property of money is utilized: Money retains its value over time and across space. *If the owner of the restaurant trusts you*, you and he can agree to delay settlement of your debt to him by giving him an appropriate amount of money later, or even later in a different location (say, his house). If the owner does not trust you (does not extend you credit), then you might have to settle the debt by giving him an assert other than money … perhaps some other valuable on your person, or maybe several hours of washing dishes in the kitchen! Or perhaps to avoid having to wash dishes, you write him a note, promising to pay him the sum you owe, and sign and date the note, and tell him he can take the note to your bank and present it to the teller and thereby be given the agreed upon sum of money. This note is called a “check”, and he has to trust that you have enough money in your bank account to be paid in full. Notice that the owner has not actually been paid until he goes to your bank to retrieve the promised sum of money. You are still in debt to him until he retrieves the money from your bank account. The check is not money, it is a written evidence of your debt to him, a written claim for the money you owe him. When he retrieves the money by giving your bank the check you wrote out and gave him, and the bank gives him the appropriate sum, that finally eliminates the debt.

Again, there are only two ways to eliminate a debt once that debt is created: The debt can either be paid off, or it can be written off. Money is what allows debt to be eliminated.

What is Currency?

I mentioned in the first paragraph that as a society evolves from “youth” through “maturity” towards “senescence” and “death”, the nature of its money and its monetary system typically changes, and these changes allow the accumulation of excessive debt throughout society which ultimately leads to systemic bankruptcy. The first of these changes is the introduction of “currency”. Currency and money are not the same thing. Currency is actually evidence of debt. Currency is a claim check for money (coins made of copper or silver of gold), just as your personal check to the restaurant was a claim check for money, money you had on deposit at your bank, waiting at your bank for you, or someone with one of your checks, to come and retrieve. Recall that the pieces of paper that we call “currency” are also sometimes called “banknotes”, just as the check you gave to the restaurant owner was a “note” you wrote to him, singed and dated by you, that he could take to your bank to get paid the money (the coins) you owed him. The difference between the piece of paper we call currency, and the piece of paper we call a personal check, is that the check is written by you, and the currency banknotes are written by the bank as sort of pre-written checks, so you don’t have to laboriously write out a personal note to your creditor, the restaurant owner. You just hand over the requisite number of banknote currency units to the restauranteur, and he can go present them to your bank and retrieve his money. And, your creditor does not have to trust that you have enough money in your account, since it is the bank, instead of you, that wrote out the banknotes your are giving him, and the bank is probably wealthier and more trustworthy than you are. It has more money in its vault than just your money. So your creditor more readily accepts the bank’s paper notes in lieu of actual money than your personal note (personal check). The bank’s paper notes, becoming familiar to many people in the community, and the bank being a trusted institution, begin to be passed hand to hand without being returned the bank to be exchanged for actual money. (The process of exchanging a banknote for money is called “redemption”: The banknote is “redeemed” for money by presenting it to the bank that issued it, and receiving money in exchange.) The bank’s paper notes begin to accumulate in people’s wallets and pass from hand to hand throughout the local economy, like water flowing in currents; thus the term “currency”. The paper banknotes were called “currency” to distinguish them from money, precious metal coins, which were “cold, hard cash”.

Step 1: Fractional Reserve Banking

The adoption of paper banknotes as a circulating medium of exchange, that is as currency, allowed money to remain safely locked away in vaults, while debts between individuals were settled by exchanging the debt notes (paper currency) issued by the banks who owned and operated those vaults. There were two immediate advantages to this scheme: First, the actual money remained securely stored away, free from being physically worn away by natural wear or by intentional loss of metal content by clipping or scratching away a tiny amount of the gold or silver while in the possession of a bad actor. Second, the paper currency banknotes, being flexible and thin and lightweight, were a bit more convenient to store and handle than heavy metal coins. So paper currency became popular, and this ability to leave actual money in the vaults of the issuing banks, allowed the banks to take advantage of another “benefit” without the widespread knowledge of the banks’ customers: The ability to create “money” out of nothing.

This process of creating “money” out of nothing is called, not “counterfeiting”, but “fractional reserve banking”. Of course, no one can create gold or silver out of nothing, so the “money” that is created by “fractional reserve banking” is an illusion. One might call it “virtual money” because it doesn’t actually exist.

When banks took in deposits of gold and silver from their customers, and issued those customers their redeemable banknotes as claim checks for the deposited money, the banks noticed that most of the time, most of the gold and silver coins simply remained in their vaults, while it was the paper currency notes which circulated. Only a small fraction of the banknotes were ever taken to the bank and redeemed for the money they represented. So the bankers decided they could simply issue more banknotes than the money they had in their vaults. They could create virtual “money” by simply printing up excess banknotes and lending these notes out to customers who wanted to borrow money. By this simple trick of printing up excess banknotes and lending them out, the bankers could earn interest on “money” they didn’t even have. This scheme for literally creating “money” out of nothing, and lending it out at interest, is extremely profitable, and everything works fine as long as most of the bank’s depositors do not come to demand their actual, real money at the same time. If that happens, the bank’s vault is emptied before all the excess banknotes have been handed in, and the depositors who still have those excess paper banknotes are out of luck: They have lost the money they originally deposited in the bank. Those unfortunate depositors who were at the end of the line of people trying to withdraw their real money from the bank, end up holding the worthless paper banknotes of a bankrupt bank whose vault has been emptied of money. When this happens, it is called a “run on the bank”, and this is the disaster that all fractional reserve banks dread happening. Non-fractional, or 100%, reserve banks, do not have this financial sword of Damocles hanging over them, because they never issue more banknotes than they have actual money in their vault. But the lure of literally being able to create “money” out of nothing, and lending that virtual “money” out at interest, is so strong that very few banks are 100% reserve banks.

Step 2: Widespread Printing of Too Much Paper Currency by Private Banks

The invention of paper currency allowed banks to create a form of virtual money (paper currency) out of nothing, and lend that paper “money” out at interest. This partially detached the production of money from the real world of physical production and consumption, and greatly enriched the banks that engaged in this “fractional reserve” lending scheme. But it came at the cost of increased risk of bankruptcy of any bank where a “bank run” should occur. The bankers increased their profits, but the depositors’ money they had deposited in the banks was now at risk of loss if a bank run occurred. And, of course, occur they did, occasionally.

Now in the economy, as in life in general, there are good times and bad. In good times, people are optimistic and tend to both spend and invest more freely than in bad times, and this economic optimism is accompanied by more lending and borrowing than in bad times. In such an optimistic period of increased lending and borrowing, money (virtual or real) is easier to obtain, and investing and spending is therefore done with less care and prudence, and as a result, people more easily make bad financial decisions that later on in hindsight are seen to have been hasty and mistaken. When the future arrives and the expected good results of their bad decision-making obtain, and revenues fall and expenses mount, the good times end and bad times ensue, and people become much more cautious and miserly, and quit borrowing and lending money as easily as in the good times. This ebb and flow of optimism and pessimism is the genesis of the “business cycle”. It is in the good times when credit expands and more loans of virtual (paper) money are made, and it is in the following bad times when credit contracts and loans of both money and paper currency are paid down or called in, or even default. And it is in bad times when people are more afraid of bank runs, which unfortunately makes bank runs more likely, in a vicious “positive feedback” loop.

One might think that the way to avoid bank runs and consequent loss of depositors’ money, is to prohibit fractional reserve banking outright, or at least make sure that depositors understand that the money they are depositing in their banks, is being lent out several times over and may be subject therefore to loss. But the lure of being able to create “money” out of nothing, at the stroke of a pen (or nowadays, the stroke of a computer key) is too strong, and any attempt to outlaw or curtail the practice, is met with stiff opposition by the banking industry. Instead, the banking industry has convinced the lawmakers and the public, to bail out banks that get into trouble, with the taxpayer’s money. To the public, the bankers promised that depositors would never again lose their money in case of a bank failure. To the politicians, the bankers promised that the government would be cut in on the flow of “virtual money” the bankers could create and lend to the government at low cost. And so, in the United States, the third step toward disconnection from economic reality was taken in 1913.

Step 3: Creation of the Federal Reserve

In the early years of the 20th century, one of the periodic banking crises caused by the mechanism I describe above, was afflicting the United States. Having created and lent out too many of their redeemable banknotes (paper currency), many banks could not meet the demands of their depositors to redeem those notes and withdraw their money (gold and silver coins), and bank failures and bank runs mounted as the nation slipped into recession. In addition, many important politicians, including president Woodrow Wilson, wanted to expand the size and activity of the federal government, in both civilian and military arenas. But this increase in government spending would not likely be supported by the American public, because the additional spending would require additional taxation. Obtaining the necessary funds another way was desirable. So the US government embarked on a search for people and institutions who would lend it money on favorable terms, just as anyone else would who wanted to increase their spending without increasing their income.

The public was afraid of losing their money in failing banks, and the politicians wanted to borrow more money. The leading bankers of that time quietly came up with a scheme to solve both of these problems, and in addition, secure themselves against failure of their own banks while earning even more profits. The idea, when pitched to the public and the politicians, emphasized the additional security and safety of depositors, and additional loans to be made available to the government, while downplaying the aspects of their proposal that directly benefited the banking industry.

The bankers’ proposal took several years to develop behind closed doors and when it was ready to be made public it was formalized as the Federal Reserve Act and was signed into law by president Wilson in late 1913. The Act created a national banking cartel and granted that cartel the right to create a single paper currency that would circulate nationally, and be accepted in payment of the newly created federal income tax.

The new American central bank, dubbed the “Federal Reserve System”, began operation in early 1914, just in time to fund America’s entry into World War 1. All federally chartered banks (that is, all banks that wished to do business across state lines) were required by the new law, to join the cartel, and follow the cartel’s rules of operation. Starting in 1914, lending to the federal government to fund America’s entry into World War 1, caused an increase in the supply of paper banknotes, and this increase in the supply of “virtual money” within a few years ignited a huge rally in the US stock market, as funds for stock speculation became much easier to obtain, and risks related to bank failures were reduced by the ability of the new Federal Reserve System to provide emergency “money” to bail out failing banks who had lent out the new “money” to excessively risky investors and stock speculators. But as we all know, bad times follow good, and the economic bubble created by the Fed’s creation of large amounts of new paper currency eventually popped. When in October 1929 this speculative bubble did pop, it created the Great Depression, which bottomed out in the mid-1930s, and set the stage for the next step away from economic reality.

Step 4: Halting Redemption of Paper Dollars for Gold Money by Americans, and Confiscation of Gold

After the 1929 stock market crash and subsequent recession, the Federal Reserve was hesitant to create too much new paper currency, and so many financial institutions failed, and businesses had difficulty obtaining bailout loans. This turned the recession into the Great Depression, which by the early 1930s was showing no signs of abating. Banks and businesses were still burdened with excess debt accumulated during the bubble of the “Roaring Twenties”. The mood of the country was pessimistic and business activity was not picking up. To relieve this debt burden, the federal government, under president Roosevelt, decided to lower the overall debt burden by devaluing the US dollar. Making each dollar less valuable would make every debtor’s debt easier to service or pay down. The way to do this, was to reduce the weight of gold of each dollar. Until then, the dollar was defined as 1/20th of an ounce of gold. By executive order, Roosevelt closed all the banks in the United States, and while the banks were closed, he ordered all Americans to turn in any money (gold coins) they had in their possession. When he reopened the banks, a person handing in their gold, as ordered, was given the dollar equivalent in paper currency. After all the gold was handed in, Roosevelt then redefined the dollar to be only 1/35thof an ounce of gold, instantly reducing the value of the dollar by almost half, and greatly easing the repayment of debts. Of course, creditors were cheated of almost half of what they were owed, but there was nothing they could do about this. After this devaluation of the dollar, gold coins were permanently withdrawn from circulation, and the money handed in to the government was melted down and cast into bars and deposited into the new gold depository built for this purpose in Fort Knox, Kentucky. This huge stockpile of gold became an asset on the books of the Federal Reserve, unavailable to Americans as money. Americans from then on had to use paper currency instead of gold coin money as their medium of exchange. Foreigners could still redeem their any paper dollars they had for gold, though. This was allowed because if the US dollar was not redeemable in actual money, no one overseas would accept dollars in payment of goods, and America would have cut itself off from all foreign trade.

Step 5: Halting Redemption of Paper Dollars for Gold Money Worldwide

Eleven years after the devaluation of the dollar and its replacement domestically by paper currency, World War 2 was drawing to a close, and the victors met at an economic summit in the little town of Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to design the post-war economic world order. America was, mainly by virtue of its not being bombed to rubble during the war, by far the wealthiest and strongest economic power in the world, with the largest gold reserves, over 20,000 metric tons of the yellow metal. At 35 dollars = 1 ounce of gold, this hoard amounted to $22 billion dollars. No other nation had anything close to such a reserve of money, so when the Bretton Woods meeting was done, the US dollar was set as the foundation of the entire world monetary system. The Federal Reserve became in effect the reserve bank of the world and the US Treasury’s gold depository became the world’s bank vault. All other national currencies were defined as fixed amounts of US dollars, and the US dollar was in turn defined as 1/35th of an ounce of gold. What this meant, was that any foreigner who presented 35 paper dollars to the US Treasury, would be given 1 ounce of gold in exchange. And other paper currencies could be redeemed for gold, by first changing those non-US currencies into US dollars, and then redeeming the resulting dollars for gold. The dollar was the “trunk of the monetary tree” and all other paper currencies were branches off that trunk, while the root of the tree was still gold, that is, was still money. In international commerce, paper currencies were still redeemable in gold, which means, redeemable for money.

The Bretton Woods monetary system put United States was in a privileged position: The US government could print paper dollars which were accepted around the world as money, since those dollars could be exchanged for gold on demand (again, except by American citizens). The US government used this privileged position to fund deficit spending, because US Treasury bonds paid the bearer of those bonds in dollars, which were redeemable in gold. If the US government wanted to spend more money in a given year than it took in in taxes, it simply issued more Treasury bonds, and those bonds were easily sold into foreign markets because the dollars they represented were directly exchangeable into gold, and gold was money everywhere.

As with private banks in past centuries, the Federal Reserve, in partnership with the federal government, using this privileged position, could not resist creating more paper dollars than the partnership had in reserve in its Fort Knox depository. By the late 1960s, only 25 years after the Bretton Woods system had been agreed to, it became obvious to anyone paying attention, that there were more paper dollars in circulation around the world than there was gold in Fort Knox. As is always the case, a bank run ensued, but this time the run was on the US Treasury. Gold began to flow out of Fort Knox at such a rapid rate that there would be none left in just a few years or even months.

The United States had abused its privilege of issuing the world’s reserve currency, and the world was calling it out. So in August 1971, before the Fort Knox depository had been completely emptied of money, president Nixon announced in a televised speech that he was “temporarily suspending convertibility of the dollar in gold or other reserve assets”. This was the United States government defaulting on its debt, and was the final step in creating the moneyless world “monetary” system we still have today.

The Global Economy, 50 Years After Removing Money From the Monetary System

When a person is in debt, he can continue participating in daily economic life, producing and consuming and selling and buying, provided he can continue to service his debt. A personal financial crisis only occurs if his debt becomes too large, relative to his income and other expenses, to continue servicing it. At that time, he suddenly defaults, and his creditor(s) lose the money they lent him, and he loses all or part of his assets. The same holds for groups of people, even large groups, who are bound together by bonds of debt.

As explained above, the transfer of money from debtor to creditor, is what eliminates debt. But money is no longer a part of our financial system. So debt can never truly be eliminated, and therefore aggregate debt must always increase, and never be reduced (except by default). And since aggregate debt must always increase, then at some point, it becomes so large it can no longer be supported, and default become inevitable.

To explain: If I owe you a debt, and I pay off that debt by giving you (gold coin) money, then my debt to you is eliminated. You now own a pure asset, namely, gold coins, which are money. This is an asset that can never have zero value, and which value does not depend on the actions of any other person. A lump of gold is an inanimate object which cannot, through any action or inaction, reneg on a promise to pay an asset. Gold is an asset and it has no “counterparty”. This is unlike, say, a share of stock or a bond, whose value depends on the production of profit by other people.

But suppose instead of giving you a gold coin, I give you a paper banknote. This eliminates my debt to you, but only provisionally. The banknote is a promise to pay, and my debt to you is only eliminated if that promise is made good by the issuer of the banknote. The banknote’s value depends on the actions of one or more other people, namely, the people that operate the bank that issued the banknote. My debt to you has not been eliminated until those other people do what they have promised they would do when presented with the banknote.

The same holds true if the banknote is issued by a government’s central bank. If I hand you paper currency, I am handing you, not an inanimate asset without a counterparty, but a central bank’s IOU. Paper currency is debt. It is debt owed ultimately by the taxpayers of the nation whose central bank issued the paper currency. In the case of the United States, when I pay you by giving you paper dollars, I am giving you debt that is serviced by the taxpayers of America. My debt to you, is eliminated by giving you more debt! Now instead of me owing you a debt, the taxpayers of American owe you a debt. And that debt bears interest, which means it is forever getting bigger, even if the US government does not add to its deficit. (But we know that the government *is* also adding to its debt beyond what interest charges accrue on its Treasury bonds.)

Note what is happening here: When I pay you in money (gold), I am giving you a pure asset, and my debt to you is eliminated. When I pay you in paper currency, I am giving you debt serviced by the taxpayers, and, while my debt to you is eliminated, the overall debt present in the US economy increases.

When president Nixon removed the ability to redeem paper currency dollars for gold (removed the ability to redeem paper central bank IOUs for money), the US dollar was the base money for the entire world. President Nixon thus removed money (gold) not just from the US economy, but from the entire world’s economy. He removed the ability to pay down aggregate debt from the entire world. When the world’s aggregate debt becomes too great for the world to support, systemic bankruptcy will occur.

How Does Systemic Bankruptcy Happen?

Systemic bankruptcy can unfold in one of two general ways. First, it can be triggered when one particular person or institution, private or public, is forced by circumstance into default. This default denies expected income to that debtor’s creditors, and those individuals or organizations are then forced into default, which in turn forces their creditors into default, and so on, in a financial chain reaction that rips through the entire economy. Bankruptcies soar and economic chaos ensues.

Or alternatively, if the person or organization that gets into trouble is “systemically important” to the economy (in practice, if they have sufficient political pull), then through channels direct or indirect, they can be bailed out with fresh currency created by the central bank. If done in time and with enough finesse, this can keep the financial chain reaction from starting, and the global financial system does not go into meltdown. This is what happened in the global financial crises of 1997-1998 and 2007-2008. In these cases, the banking and political elites managed to keep their system going, but only at the expense of creating even more paper currency, and more taxpayer supported debt.

Global rounds of bailouts like those that occurred in 1998 and 2008 do not eliminate any debt, and so do not solve the problem of systemic debt. Instead, such bailouts only grow the amount of aggregate debt while temporarily keeping the system going. Eventually, the debt burden gets so large, that an attempted bailout cannot be pulled off, and systemic bankruptcy occurs.

Or, the accelerating rate of currency creation pushes so much paper currency into the global economy, that the value of each currency unit collapses, people lose confidence in the value of their paper currency, and the system suffers hyperinflationary collapse.

What are the Consequences of Systemic Bankruptcy?

Systemic bankruptcy involves the near-simultaneous bankruptcy of many people and organizations, along with a collapse in the value of the paper currency. This causes widespread interruption of production and trade, and a great increase in economic misery. This can cause social and political instability up to and including civil unrest and war, and a general derangement of social and economic relations.

Can Systemic Bankruptcy be Avoided?

Once a society (or in the present case, the entire globalized world) reaches its tipping point of too much aggregate debt, some form of systemic bankruptcy becomes inevitable. The best outcome for our current situation, would be to do something like what was done in the US in the 1930s: Quit running government budget deficits, so as to avoid creating more aggregate debt, while formally devaluing the US dollar, to allow people to start paying down their heavy debt burden without many individual defaults. This is in effect, recognizing that we cannot pay down our aggregate debts, and spreading the resulting losses amongst all holders of that debt. After the formal devaluation, which would define the dollar as a new, smaller weight of gold, gold would again be allowed to circulate, and thereby perform its function of eliminating debt.

The alternative, is to keep printing more currency to perform ever larger and more numerous bailouts of well-connected people and institutions, which will result in the total destruction of the value of the dollar. This path puts the losses onto the backs of people who have built up savings in the form of bank accounts and bonds, and transfers vast amounts of wealth to the few who are politically well connected.

How Can Systemic Bankruptcy be Kept from Recurring?

Our current global fiat currency system is inherently unstable because it contains no mechanism to eliminate systemic debt except through default and bankruptcy.

The chaos caused by systemic bankruptcy is an existential threat to our civilization. If we can pass through this present “great financial filter” we will need to keep it from ever happening again. Since systemic bankruptcy is caused by accumulation of excess systemic debt, and transfer of gold (money) from person to person is the only mechanism (other than widespread default) that eliminates systemic debt, the only way to avoid systemic bankruptcy in the future, is to always allow gold to circulate in the hands of the people.

The gold must flow.

How Can I Prepare for Systemic Bankruptcy?

When one knows a storm is approaching, one can take prudent measures to prepare to weather that storm. If the storm is a hurricane, you can stock up on essentials and emergency supplies, put away outdoor furniture, put plywood on the windows, fill the bathtub with water, and prepare to help out neighbors and friends during and after the storm.

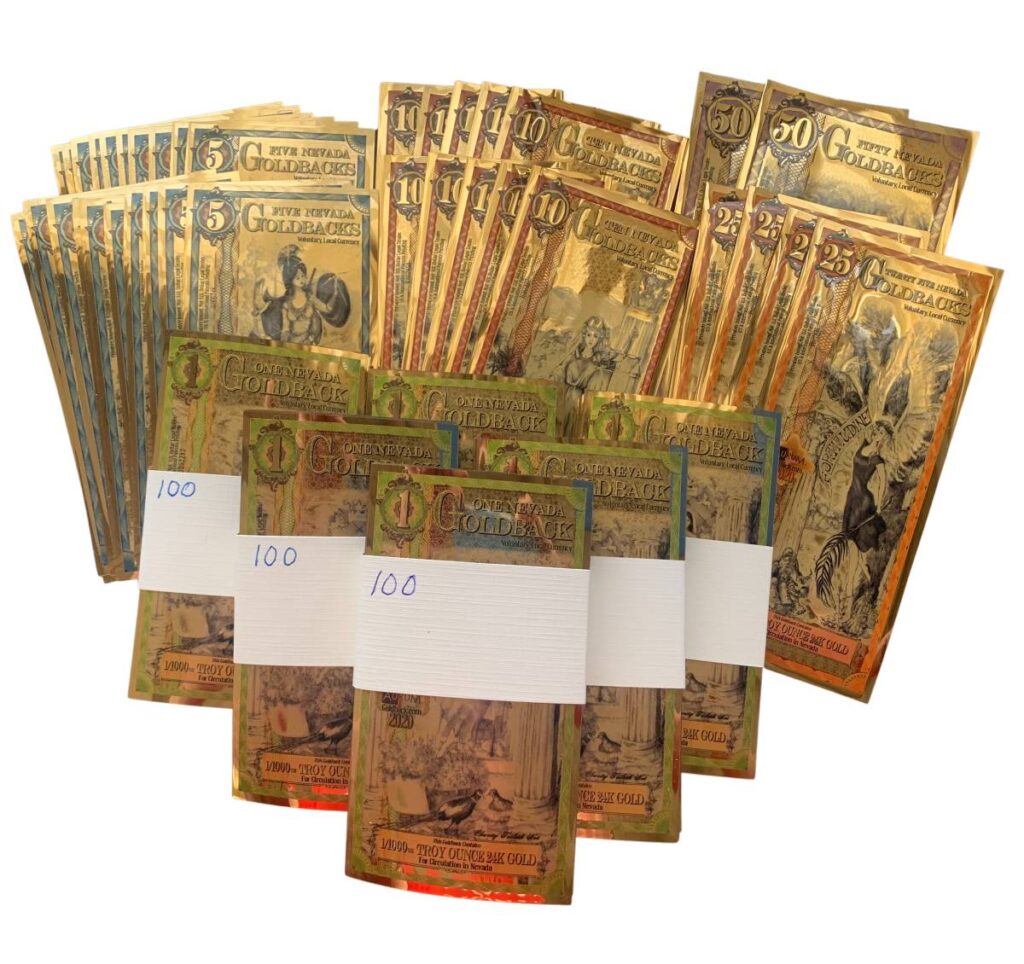

Similarly for an economic storm. Take inventory of your pantry and add to it if necessary. Make sure you have plenty of whatever you use on a daily basis, should supply chains be disrupted and shortages develop. And for this particular type of storm, convert some of your paper financial savings, into money, that is, into gold and silver, with some of that being in easily spendable form such as Goldbacks.

And finally, keep close to trusted family and friends. They are the absolute best assets to have in hard times.